Paul Klee

(Münchenbuchsee near Bern 1879–1940 Muralto)

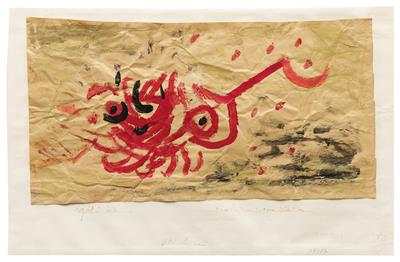

‘Praeludium zu einem Ständchen’ (Prelude to a Serenade), 1940, signed, titled, dated, inscribed Klee 1940 L7, coloured paste on wrinkled wrapping paper on light cardboard, 23 x 44 cm, framed

Provenance:

Werner Allenbach (1903-1975), Berne until 1952

Galerie Rosengart, Lucerne (1952–1953)

Christoph Bernoulli (1897-1981), Basel since 1953 - acquired at Galerie Rosengart 1953

Galerie Vömel, Düsseldorf - acquired there by the present owner (gallery label on the reverse)

Private Collection, Germany

Literature:

Karl Ruhrberg, Der Schlüssel der Malerei von heute, Düsseldorf/ Vienna 1965, p. 192/193 (col. ill.)

Josef Helfenstein, Stefan Frey, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 232, no 254

Paul Klee Stiftung Bern (ed.), Paul Klee, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol 9, 1940, Bern 2004, p. 174, no 9286

Exhibited:

Ca Pesaro, Venice / Palazzo Reale Milan 1986, Paul Klee nelle collezioni private, no 153

Kunstmuseum Bern 1990, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr,

Schloss Moyland, Bedburg-Hau 2000/ Kurpfälzisches Museum der Stadt Heidelberg 2002, Paul Klee trifft Joseph Beuys, Ein Fetzen Gemeinschaft , cat. no 187, p. 324 (col. ill.)

„nulla dies sine linea – no day without a line“

Paul Klee 1938

„The picture... has no particular purpose. It is a purposeless affair that only has one goal, that of making us happy. That is something quite different from the relationship to external life... It should be something that involves us, that we gladly often look at, that we ultimately would like to possess.“

Petra Petitpierre, Aus der Malklasse Paul Klee, Bern 1957, p. 32

In his last creative year, 1940, Paul Klee no longer divided his creative catalogue according to years, as he had done in previous years, but he now was reckoning in months – he clearly saw the end was approaching. Already before his departure for a cure in Tessin in May 1940, Klee was able to record 366 pictures in his catalogue of works – producing one work for each day of the leap year ahead.

The titles of the pictures from the year 1940 no longer name the object, as they had previously done; they refer to it. The titles of his works are to be experienced intuitively rather than construed intellectually. They themselves require interpretation and are accompanied by numbers and letters which indicate the running number, the category of work, the code number, the technique and the painting ground as well as the title. For the entries in the catalogue of his works, Paul Klee began in 1940 with the letter „Z“ for the code number. Each time, 20 works were bundled on one page of the work book under one letter, so that the work catalogue, written in his own hand in May 1940, ends with the work 366 with „E“. The numerical increase of the work numbers stands in diametrically opposed symmetry to the backwards-running alphabet. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ bears the running number 269 and the code number L 7 from the year 1940. The equally important organising and preservation of the paintings and drawings completes the process: Paul Klee organises all his sheets on thin cardboard, and gives them a title and inventory number; this makes him not only an artist but also an interpreter and registrar of his work.

Paul Klee always understood himself to be an observer, an interpreter of his own work. „ ‘I am ultimately a beholder and give myself a present.’ What he sees in a work of art would be therefore only one interpretation, not its significance, which is up to the viewer to discover. The work is therefore not to be viewed as a personal statement of the artist (...), the completed picture leads its own life, independent of the personal associations that it may have held for its creator.“(Josef Helfenstein/ Stefan Frey (eds.), Paul Klee, Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 29).

Paul Klee attempted to fix in an artistic manner the visions that beset him during the last year of his life; he was best able to do this in the spontaneous and spiritual medium of drawing. The unbelievable productivity of the year 1940 required that Klee work with a variety of materials which were available to him. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ is painted on a crumpled-up piece of paper, whereby the haptic quality of the painted surface is additionally overemphasised and the painting is consciously suspended in an almost three-dimensional space.

His works represent a novelty in the history of the technique of painting: „His painting rests on a provocation of matter.“ (ibid. 82) „It takes place in the sense of a spiritualisation and at the same time takes into account material decay. Probably ‘mortification’ is inherent (...) in Klee‘s paintings. To encounter them outside a historical consciousness would mean accepting the work of art as a ruin, without however turning historical issues into philosophical verisimilitudes. Therein exists a material actuality in Klee’s art, perhaps precisely the one he created at the end of his life.“ (ibid. p. 90).

Provenance:

Werner Allenbach (1903-1975), Berne until 1952

Galerie Rosengart, Luzern (1952–1953)

Christoph Bernoulli (1897-1981), Basel since 1953 - acquired at Galerie Rosengart 1953

Galerie Vömel, Düsseldorf - acquired there by the present owner (gallery label on the reverse)

Private Collection, Germany

Literature:

Karl Ruhrberg, Der Schlüssel der Malerei von heute, Düsseldorf/ Vienna 1965, p. 192/193 (col. ill.)

Josef Helfenstein, Stefan Frey, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 232, no 254

Paul Klee Stiftung Bern (ed.), Paul Klee, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol 9, 1940, Bern 2004, p. 174, no 9286

Exhibited:

Ca Pesaro, Venice / Palazzo Reale Milan 1986, Paul Klee nelle collezioni private, no 153

Kunstmuseum Bern 1990, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr,

Schloss Moyland, Bedburg-Hau 2000/ Kurpfälzisches Museum der Stadt Heidelberg 2002, Paul Klee trifft Joseph Beuys, Ein Fetzen Gemeinschaft , cat. no 187, p. 324 (col. ill.)

„nulla dies sine linea – no day without a line“

Paul Klee 1938

„The picture... has no particular purpose. It is a purposeless affair that only has one goal, that of making us happy. That is something quite different from the relationship to external life... It should be something that involves us, that we gladly often look at, that we ultimately would like to possess.“

Petra Petitpierre, Aus der Malklasse Paul Klee, Bern 1957, p. 32

In his last creative year, 1940, Paul Klee no longer divided his creative catalogue according to years, as he had done in previous years, but he now was reckoning in months – he clearly saw the end was approaching. Already before his departure for a cure in Tessin in May 1940, Klee was able to record 366 pictures in his catalogue of works – producing one work for each day of the leap year ahead.

The titles of the pictures from the year 1940 no longer name the object, as they had previously done; they refer to it. The titles of his works are to be experienced intuitively rather than construed intellectually. They themselves require interpretation and are accompanied by numbers and letters which indicate the running number, the category of work, the code number, the technique and the painting ground as well as the title. For the entries in the catalogue of his works, Paul Klee began in 1940 with the letter „Z“ for the code number. Each time, 20 works were bundled on one page of the work book under one letter, so that the work catalogue, written in his own hand in May 1940, ends with the work 366 with „E“. The numerical increase of the work numbers stands in diametrically opposed symmetry to the backwards-running alphabet. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ bears the running number 269 and the code number L 7 from the year 1940. The equally important organising and preservation of the paintings and drawings completes the process: Paul Klee organises all his sheets on thin cardboard, and gives them a title and inventory number; this makes him not only an artist but also an interpreter and registrar of his work.

Paul Klee always understood himself to be an observer, an interpreter of his own work. „ ‘I am ultimately a beholder and give myself a present.’ What he sees in a work of art would be therefore only one interpretation, not its significance, which is up to the viewer to discover. The work is therefore not to be viewed as a personal statement of the artist (...), the completed picture leads its own life, independent of the personal associations that it may have held for its creator.“(Josef Helfenstein/ Stefan Frey (eds.), Paul Klee, Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 29).

Paul Klee attempted to fix in an artistic manner the visions that beset him during the last year of his life; he was best able to do this in the spontaneous and spiritual medium of drawing. The unbelievable productivity of the year 1940 required that Klee work with a variety of materials which were available to him. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ is painted on a crumpled-up piece of paper, whereby the haptic quality of the painted surface is additionally overemphasised and the painting is consciously suspended in an almost three-dimensional space.

His works represent a novelty in the history of the technique of painting: „His painting rests on a provocation of matter.“ (ibid. 82) „It takes place in the sense of a spiritualisation and at the same time takes into account material decay. Probably ‘mortification’ is inherent (...) in Klee‘s paintings. To encounter them outside a historical consciousness would mean accepting the work of art as a ruin, without however turning historical issues into philosophical verisimilitudes. Therein exists a material actuality in Klee’s art, perhaps precisely the one he created at the end of his life.“ (ibid. p. 90).

23.11.2016 - 17:00

- Odhadní cena:

-

EUR 220.000,- do EUR 240.000,-

Paul Klee

(Münchenbuchsee near Bern 1879–1940 Muralto)

‘Praeludium zu einem Ständchen’ (Prelude to a Serenade), 1940, signed, titled, dated, inscribed Klee 1940 L7, coloured paste on wrinkled wrapping paper on light cardboard, 23 x 44 cm, framed

Provenance:

Werner Allenbach (1903-1975), Berne until 1952

Galerie Rosengart, Lucerne (1952–1953)

Christoph Bernoulli (1897-1981), Basel since 1953 - acquired at Galerie Rosengart 1953

Galerie Vömel, Düsseldorf - acquired there by the present owner (gallery label on the reverse)

Private Collection, Germany

Literature:

Karl Ruhrberg, Der Schlüssel der Malerei von heute, Düsseldorf/ Vienna 1965, p. 192/193 (col. ill.)

Josef Helfenstein, Stefan Frey, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 232, no 254

Paul Klee Stiftung Bern (ed.), Paul Klee, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol 9, 1940, Bern 2004, p. 174, no 9286

Exhibited:

Ca Pesaro, Venice / Palazzo Reale Milan 1986, Paul Klee nelle collezioni private, no 153

Kunstmuseum Bern 1990, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr,

Schloss Moyland, Bedburg-Hau 2000/ Kurpfälzisches Museum der Stadt Heidelberg 2002, Paul Klee trifft Joseph Beuys, Ein Fetzen Gemeinschaft , cat. no 187, p. 324 (col. ill.)

„nulla dies sine linea – no day without a line“

Paul Klee 1938

„The picture... has no particular purpose. It is a purposeless affair that only has one goal, that of making us happy. That is something quite different from the relationship to external life... It should be something that involves us, that we gladly often look at, that we ultimately would like to possess.“

Petra Petitpierre, Aus der Malklasse Paul Klee, Bern 1957, p. 32

In his last creative year, 1940, Paul Klee no longer divided his creative catalogue according to years, as he had done in previous years, but he now was reckoning in months – he clearly saw the end was approaching. Already before his departure for a cure in Tessin in May 1940, Klee was able to record 366 pictures in his catalogue of works – producing one work for each day of the leap year ahead.

The titles of the pictures from the year 1940 no longer name the object, as they had previously done; they refer to it. The titles of his works are to be experienced intuitively rather than construed intellectually. They themselves require interpretation and are accompanied by numbers and letters which indicate the running number, the category of work, the code number, the technique and the painting ground as well as the title. For the entries in the catalogue of his works, Paul Klee began in 1940 with the letter „Z“ for the code number. Each time, 20 works were bundled on one page of the work book under one letter, so that the work catalogue, written in his own hand in May 1940, ends with the work 366 with „E“. The numerical increase of the work numbers stands in diametrically opposed symmetry to the backwards-running alphabet. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ bears the running number 269 and the code number L 7 from the year 1940. The equally important organising and preservation of the paintings and drawings completes the process: Paul Klee organises all his sheets on thin cardboard, and gives them a title and inventory number; this makes him not only an artist but also an interpreter and registrar of his work.

Paul Klee always understood himself to be an observer, an interpreter of his own work. „ ‘I am ultimately a beholder and give myself a present.’ What he sees in a work of art would be therefore only one interpretation, not its significance, which is up to the viewer to discover. The work is therefore not to be viewed as a personal statement of the artist (...), the completed picture leads its own life, independent of the personal associations that it may have held for its creator.“(Josef Helfenstein/ Stefan Frey (eds.), Paul Klee, Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 29).

Paul Klee attempted to fix in an artistic manner the visions that beset him during the last year of his life; he was best able to do this in the spontaneous and spiritual medium of drawing. The unbelievable productivity of the year 1940 required that Klee work with a variety of materials which were available to him. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ is painted on a crumpled-up piece of paper, whereby the haptic quality of the painted surface is additionally overemphasised and the painting is consciously suspended in an almost three-dimensional space.

His works represent a novelty in the history of the technique of painting: „His painting rests on a provocation of matter.“ (ibid. 82) „It takes place in the sense of a spiritualisation and at the same time takes into account material decay. Probably ‘mortification’ is inherent (...) in Klee‘s paintings. To encounter them outside a historical consciousness would mean accepting the work of art as a ruin, without however turning historical issues into philosophical verisimilitudes. Therein exists a material actuality in Klee’s art, perhaps precisely the one he created at the end of his life.“ (ibid. p. 90).

Provenance:

Werner Allenbach (1903-1975), Berne until 1952

Galerie Rosengart, Luzern (1952–1953)

Christoph Bernoulli (1897-1981), Basel since 1953 - acquired at Galerie Rosengart 1953

Galerie Vömel, Düsseldorf - acquired there by the present owner (gallery label on the reverse)

Private Collection, Germany

Literature:

Karl Ruhrberg, Der Schlüssel der Malerei von heute, Düsseldorf/ Vienna 1965, p. 192/193 (col. ill.)

Josef Helfenstein, Stefan Frey, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 232, no 254

Paul Klee Stiftung Bern (ed.), Paul Klee, Catalogue Raisonné, Vol 9, 1940, Bern 2004, p. 174, no 9286

Exhibited:

Ca Pesaro, Venice / Palazzo Reale Milan 1986, Paul Klee nelle collezioni private, no 153

Kunstmuseum Bern 1990, Paul Klee - Das Schaffen im Todesjahr,

Schloss Moyland, Bedburg-Hau 2000/ Kurpfälzisches Museum der Stadt Heidelberg 2002, Paul Klee trifft Joseph Beuys, Ein Fetzen Gemeinschaft , cat. no 187, p. 324 (col. ill.)

„nulla dies sine linea – no day without a line“

Paul Klee 1938

„The picture... has no particular purpose. It is a purposeless affair that only has one goal, that of making us happy. That is something quite different from the relationship to external life... It should be something that involves us, that we gladly often look at, that we ultimately would like to possess.“

Petra Petitpierre, Aus der Malklasse Paul Klee, Bern 1957, p. 32

In his last creative year, 1940, Paul Klee no longer divided his creative catalogue according to years, as he had done in previous years, but he now was reckoning in months – he clearly saw the end was approaching. Already before his departure for a cure in Tessin in May 1940, Klee was able to record 366 pictures in his catalogue of works – producing one work for each day of the leap year ahead.

The titles of the pictures from the year 1940 no longer name the object, as they had previously done; they refer to it. The titles of his works are to be experienced intuitively rather than construed intellectually. They themselves require interpretation and are accompanied by numbers and letters which indicate the running number, the category of work, the code number, the technique and the painting ground as well as the title. For the entries in the catalogue of his works, Paul Klee began in 1940 with the letter „Z“ for the code number. Each time, 20 works were bundled on one page of the work book under one letter, so that the work catalogue, written in his own hand in May 1940, ends with the work 366 with „E“. The numerical increase of the work numbers stands in diametrically opposed symmetry to the backwards-running alphabet. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ bears the running number 269 and the code number L 7 from the year 1940. The equally important organising and preservation of the paintings and drawings completes the process: Paul Klee organises all his sheets on thin cardboard, and gives them a title and inventory number; this makes him not only an artist but also an interpreter and registrar of his work.

Paul Klee always understood himself to be an observer, an interpreter of his own work. „ ‘I am ultimately a beholder and give myself a present.’ What he sees in a work of art would be therefore only one interpretation, not its significance, which is up to the viewer to discover. The work is therefore not to be viewed as a personal statement of the artist (...), the completed picture leads its own life, independent of the personal associations that it may have held for its creator.“(Josef Helfenstein/ Stefan Frey (eds.), Paul Klee, Das Schaffen im Todesjahr, Stuttgart 1990, p. 29).

Paul Klee attempted to fix in an artistic manner the visions that beset him during the last year of his life; he was best able to do this in the spontaneous and spiritual medium of drawing. The unbelievable productivity of the year 1940 required that Klee work with a variety of materials which were available to him. „Praeludium zu einem Ständchen“ is painted on a crumpled-up piece of paper, whereby the haptic quality of the painted surface is additionally overemphasised and the painting is consciously suspended in an almost three-dimensional space.

His works represent a novelty in the history of the technique of painting: „His painting rests on a provocation of matter.“ (ibid. 82) „It takes place in the sense of a spiritualisation and at the same time takes into account material decay. Probably ‘mortification’ is inherent (...) in Klee‘s paintings. To encounter them outside a historical consciousness would mean accepting the work of art as a ruin, without however turning historical issues into philosophical verisimilitudes. Therein exists a material actuality in Klee’s art, perhaps precisely the one he created at the end of his life.“ (ibid. p. 90).

|

Horká linka kupujících

Po-Pá: 10.00 - 17.00

kundendienst@dorotheum.at +43 1 515 60 200 |

| Aukce: | Moderní |

| Typ aukce: | Salónní aukce |

| Datum: | 23.11.2016 - 17:00 |

| Místo konání aukce: | Wien | Palais Dorotheum |

| Prohlídka: | 12.11. - 23.11.2016 |

Všechny objekty umělce