Bicci di Lorenzo

(Florence, circa 1368–1452)

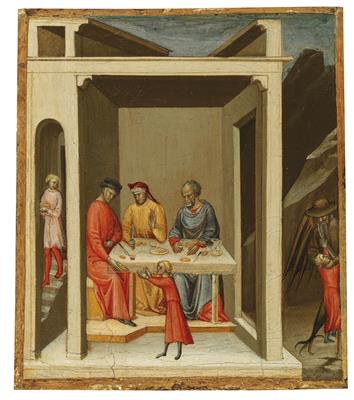

A scene from the life of Saint Nicholas: The miracle of a child restored to his parents,

tempera on panel, 31.5 x 27.5 cm, including baton edges, framed

Inscribed on the reverse: Il Vampiro/ Vampiro che strozza un fanciullo mentre i suoi parenti stanno seduti a mensa/ (Intorno ai Vampiri e agli scrittori che ne hanno parlato può leggersi il Tiraboschi nella storia letteraria d’Italia)

Provenance:

Monastery of San Niccolò in Cafaggio, Florence, 1433-1787;

acquired in 1787 by Marchese Alfonso Tacoli Canacci, Parma (according to literature, see Chiodo);

Prince Trivulzio, Milan;

Private collection, New York, 1957;

with Wildenstein, New York;

Private collection, United Kingdom;

sale, Christie’s, London, 9 July 2003, lot 75 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

where acquired by the present owner

Exhibited:

Arezzo, Basilica Inferiore di San Francesco, Il primato dei Toscani nelle Vite del Vasari, 3 September 2011 – 9 January 2012 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

Tokyo, The Bunkamura Museum of Art, Money and Beauty: Botticelli and the Renaissance in Florence, 21 March – 28 June 2015, no. 40 (as Bicci di Lorenzo)

Literature:

F. Zeri, Una precisazione su Bicci di Lorenzo, in: Paragone, no. 105, September 1958, pp. 70-71, fig. 48 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements circa 25 x 21 cm);

W. Cohn, Maestri sconosciuti del Quattrocentro fiorentino: II. - Stefano d’Antonio, in: Bollettino d’arte, XLIV, no. 1, January – March 1959, pp. 61, 68, note 4 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

F. Zeri/E. E. Gardner, Italian Paintings. A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Florentine School, New York 1971, mentioned p. 70 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

C. Lloyd, A Catalogue of Earlier Italian Paintings in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1977, p. 33, mentioned note 7 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements 25 x 21 cm);

J. Pope-Hennessy, Italian Paintings in the Robert Lehman Collection, Princeton 1987, p. 173, mentioned under no. 73 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

F. Petrucci, in: F. Zeri (ed.), La Pittura in Italia: Il Quattrocento, 2nd edition, Milan 1987, vol. 2, p. 585 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

F. Zeri, in: Giorno per giorno nella pittura: scritti sull’arte toscana dal Trecento al primo Cinquecento, Turin 1991, pp. 142-143, fig. 213 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements circa 25 x 21 cm);

S. Chiodo, Osservazioni su due polittici di Bicci di Lorenzo, in: Arte Cristiana, 2000, no. 799, pp. 269–280, fig. 4 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements 25 x 21 cm);

L. Lorenzi, Devils in Art: Florence from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, 2nd edition, Florence 2006, no page (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

K. Christiansen, in: L. Laureati/L. Mochi Onori (eds.), Gentile da Fabriano e l’altro Rinascimento, exhibition catalogue, Milan 2006, p. 288, mentioned under no. VI. 13 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

P. Refice, in: P. Refice (ed.), Il primato dei Toscani nelle Vite del Vasari, exhibition catalogue, Ospedaletto 2011, pp. 274-275, ill. (as Bicci di Lorenzo, but erroneously mentioned as by Neri di Bicci in the entry);

L. Sebregondi, in: L Sebregondi (ed.), Money and Beauty: Botticelli and the Renaissance in Florence, exhibition catalogue, Bunkamura 2015, pp. 88-89, no. 40, ill. (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

A. Degasperi, Arte nell’arte: Ceramiche medievali lette attraverso gli occhi dei grandi maestri toscani del Trecento e del Quattrocento, Florence 2016, p. 38, reproduced on cover and p. 41, figs. 13-14 (as Bicci di Lorenzo)

The present painting is registered in the Fototeca Zeri under no. 10322 (as Bicci di Lorenzo).

This panel originally belonged to the predella of a polyptych commissioned from Bicci di Lorenzo and his ‘companion’ [‘compagno’] Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni, for the high altar of the monastery church of San Niccolò in Cafaggio in Florence. The work was created in around 1433 and it was certainly completed by 1435 when it was valued by Beato Angelico and Rossello di Jacopo Franchi (see Cohn in literature, p. 61). The polyptych was still in situ in 1758 when it was recorded by Richa who, however, only commented on the principal panels (see G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, vol. 7, Florence 1758, p. 35, as Lorenzo di Bicci). In 1787 the polyptych was dismembered and dispersed.

The central panel consisted of the Madonna and Child with four Angels, (now in the Galleria Nazionale, Parma) which was flanked, on the left, by a Saint Benedict and Saint Nicholas of Bari (Museo del Monumento Nazionale della Badia Greca, Grottaferrata – this panel was probably made by Stefano d’Antonio, see Pope-Hennessy in literature) and on the right, by a panel representing Saint John the Baptist and Saint Matthew (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Initiated by the studies conducted by Federico Zeri (see Zeri 1958 in literature), attempts have been made to reconstruct the predella which accompanied the polyptych. This probably consisted of seven panels representing the life of Saint Nicholas, of these, six have been identified and were probably arranged in the following order from left to right: The Birth of Saint Nicholas (formerly in the Barbara Piasecka Johnson collection, and sold at Sotheby’s, London, 8 July 2009, lot 1), the present panel, Saint Nicholas providing dowries (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Saint Nicholas rescuing sailors in a storm (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), Saint Nicholas resuscitating three youths (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), A miracle at the tomb of Saint Nicholas (Wawel State Collection, Kraków).

Additionally, various figures of Saints decorated the lateral piers of the polyptych and there was probably an order over the main panels (see Chiodo in Literature).

The present painting represents the first part of a miracle as told by Jacopo da Varagine in the Golden Legend, a text broadly circulated in the Middle Ages and Renaissance which served as iconographic inspiration to numerous artists. The narrative describes a banquet arranged by a rich Florentine merchant in honour of his patron, Saint Nicholas, for the intention of securing the saint’s protection for his student son. During the banquet a mendicant presented himself at the door begging for charity. The merchant’s young son left the house to fetch him some bread but as we see on the right hand side of the present panel, the beggar revealed himself to be the devil and strangled the youth.

The conclusion of the story was probably represented on a further (currently missing) panel, and might have shown the father beseeching the pity of Saint Nicholas, and attaining the resurrection of his son in exchange for his great faith.

The episode is narrated with lively fluidity: the slender elongated figures harmonise with the architecture they occupy and are similar to those of the five other panels that originally formed the predella.

Bicci di Lorenzo’s polyptych relates iconographically to another example made by Gentile da Fabriano in 1425 for the Quaratesi chapel in San Niccolò Oltrarno (of which the central panels are preserved in the Uffizi, while the predella is divided between the Pinacoteca Vaticana and the National Gallery of Art, Washington), however, the predella by Gentile consists of only five scenes and lacks the episode represented in the present panel.

Bicci di Lorenzo trained in Florence in the studio of his father, Lorenzo di Bicci, during the final decade of the Trecento. In 1404 he enrolled in the Guild of Doctors and Herbalists or Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali and took over his father’s business. He directed a successful studio that was subsequently managed by his son Neri di Bicci; he developed a pictorial language which found great favour amongst his patrons and achieved a fusion between the traditions of the Trecento while gradually making way for the innovations of the Renaissance.

Technical analysis by Gianluca Poldi:

IR reflectography, carried out in two different IR bands, show the existence of a linear underdrawing to outline the architecture and the figures, made with a small paintbrush with black or grey or brown ink over the white preparatory ground. Optical microscopy images suggest the ink used to draw the figures and their detailed faces is brown, containing earths, rather than black.

The modelling of the faces is refined, the painter starts from a partial priming similar to the “verdaccio” described by Cennino Cennini in “The Book of the Art”, he then worked with the brownish under-drawing for various features such as eyes, nose and mouth, and then the artist added some “stains” of colour in three tones of flesh, made with lead white, mixed with vermillion in different proportions: whitish, pink and reddish. Then brown lines were added to define features, the border of the lips and the eyes, the latter finished with black and white.

A few small changes can be noticed, such as in the hands of the central boy dressed in red, on the shoulder/back of the man without a hat and in the hat of the central man with a knife, which was originally different, with a type of scalloped edge. Small corrections were also made in the architecture and the space for the figures: the young blonde figure on the left is partially painted over the architecture of the background door and the staircase. Small holes can be noticed in the paint surface, due to very small bubbles in the mixtures. The tempera hatches are evident in the figures, especially in the lights of the clothes, while the building is obtained with flat continuous brushstrokes.

Unusual features include: the dark brown of the roof made by spreading a layer of finely-ground brown earths over a vermilion red base, with lumps; and there is an unexpected use of red lake to make the shadows of the yellow robe of the central figure. Besides ochre and brown earths, vermillion in brighter reds, and a coccid-derived red lake (presumably kermes) for the pink colour of the boy’s garment on the right and for the shadows, the palette includes lead-tin yellow in the central male figure and natural ultramarine (lapis lazuli) in all the blue areas, comprising the sky and the man´s hat on the left. Small amounts of iron oxides can be found both in the sky, mixed with the lead white and lapis lazuli, and in the cloak of the man at the right of the table, together with some grains of red lake. A few blue and green particles can be found mixed with the pink zones to slightly change the colour.

Esperto: Mark MacDonnell

Mark MacDonnell

Mark MacDonnell

+43 1 515 60 403

oldmasters@dorotheum.com

10.11.2020 - 16:00

- Stima:

-

EUR 150.000,- a EUR 200.000,-

Bicci di Lorenzo

(Florence, circa 1368–1452)

A scene from the life of Saint Nicholas: The miracle of a child restored to his parents,

tempera on panel, 31.5 x 27.5 cm, including baton edges, framed

Inscribed on the reverse: Il Vampiro/ Vampiro che strozza un fanciullo mentre i suoi parenti stanno seduti a mensa/ (Intorno ai Vampiri e agli scrittori che ne hanno parlato può leggersi il Tiraboschi nella storia letteraria d’Italia)

Provenance:

Monastery of San Niccolò in Cafaggio, Florence, 1433-1787;

acquired in 1787 by Marchese Alfonso Tacoli Canacci, Parma (according to literature, see Chiodo);

Prince Trivulzio, Milan;

Private collection, New York, 1957;

with Wildenstein, New York;

Private collection, United Kingdom;

sale, Christie’s, London, 9 July 2003, lot 75 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

where acquired by the present owner

Exhibited:

Arezzo, Basilica Inferiore di San Francesco, Il primato dei Toscani nelle Vite del Vasari, 3 September 2011 – 9 January 2012 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

Tokyo, The Bunkamura Museum of Art, Money and Beauty: Botticelli and the Renaissance in Florence, 21 March – 28 June 2015, no. 40 (as Bicci di Lorenzo)

Literature:

F. Zeri, Una precisazione su Bicci di Lorenzo, in: Paragone, no. 105, September 1958, pp. 70-71, fig. 48 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements circa 25 x 21 cm);

W. Cohn, Maestri sconosciuti del Quattrocentro fiorentino: II. - Stefano d’Antonio, in: Bollettino d’arte, XLIV, no. 1, January – March 1959, pp. 61, 68, note 4 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

F. Zeri/E. E. Gardner, Italian Paintings. A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Florentine School, New York 1971, mentioned p. 70 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

C. Lloyd, A Catalogue of Earlier Italian Paintings in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1977, p. 33, mentioned note 7 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements 25 x 21 cm);

J. Pope-Hennessy, Italian Paintings in the Robert Lehman Collection, Princeton 1987, p. 173, mentioned under no. 73 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

F. Petrucci, in: F. Zeri (ed.), La Pittura in Italia: Il Quattrocento, 2nd edition, Milan 1987, vol. 2, p. 585 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

F. Zeri, in: Giorno per giorno nella pittura: scritti sull’arte toscana dal Trecento al primo Cinquecento, Turin 1991, pp. 142-143, fig. 213 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements circa 25 x 21 cm);

S. Chiodo, Osservazioni su due polittici di Bicci di Lorenzo, in: Arte Cristiana, 2000, no. 799, pp. 269–280, fig. 4 (as Bicci di Lorenzo, with measurements 25 x 21 cm);

L. Lorenzi, Devils in Art: Florence from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, 2nd edition, Florence 2006, no page (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

K. Christiansen, in: L. Laureati/L. Mochi Onori (eds.), Gentile da Fabriano e l’altro Rinascimento, exhibition catalogue, Milan 2006, p. 288, mentioned under no. VI. 13 (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

P. Refice, in: P. Refice (ed.), Il primato dei Toscani nelle Vite del Vasari, exhibition catalogue, Ospedaletto 2011, pp. 274-275, ill. (as Bicci di Lorenzo, but erroneously mentioned as by Neri di Bicci in the entry);

L. Sebregondi, in: L Sebregondi (ed.), Money and Beauty: Botticelli and the Renaissance in Florence, exhibition catalogue, Bunkamura 2015, pp. 88-89, no. 40, ill. (as Bicci di Lorenzo);

A. Degasperi, Arte nell’arte: Ceramiche medievali lette attraverso gli occhi dei grandi maestri toscani del Trecento e del Quattrocento, Florence 2016, p. 38, reproduced on cover and p. 41, figs. 13-14 (as Bicci di Lorenzo)

The present painting is registered in the Fototeca Zeri under no. 10322 (as Bicci di Lorenzo).

This panel originally belonged to the predella of a polyptych commissioned from Bicci di Lorenzo and his ‘companion’ [‘compagno’] Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni, for the high altar of the monastery church of San Niccolò in Cafaggio in Florence. The work was created in around 1433 and it was certainly completed by 1435 when it was valued by Beato Angelico and Rossello di Jacopo Franchi (see Cohn in literature, p. 61). The polyptych was still in situ in 1758 when it was recorded by Richa who, however, only commented on the principal panels (see G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, vol. 7, Florence 1758, p. 35, as Lorenzo di Bicci). In 1787 the polyptych was dismembered and dispersed.

The central panel consisted of the Madonna and Child with four Angels, (now in the Galleria Nazionale, Parma) which was flanked, on the left, by a Saint Benedict and Saint Nicholas of Bari (Museo del Monumento Nazionale della Badia Greca, Grottaferrata – this panel was probably made by Stefano d’Antonio, see Pope-Hennessy in literature) and on the right, by a panel representing Saint John the Baptist and Saint Matthew (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Initiated by the studies conducted by Federico Zeri (see Zeri 1958 in literature), attempts have been made to reconstruct the predella which accompanied the polyptych. This probably consisted of seven panels representing the life of Saint Nicholas, of these, six have been identified and were probably arranged in the following order from left to right: The Birth of Saint Nicholas (formerly in the Barbara Piasecka Johnson collection, and sold at Sotheby’s, London, 8 July 2009, lot 1), the present panel, Saint Nicholas providing dowries (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Saint Nicholas rescuing sailors in a storm (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), Saint Nicholas resuscitating three youths (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), A miracle at the tomb of Saint Nicholas (Wawel State Collection, Kraków).

Additionally, various figures of Saints decorated the lateral piers of the polyptych and there was probably an order over the main panels (see Chiodo in Literature).

The present painting represents the first part of a miracle as told by Jacopo da Varagine in the Golden Legend, a text broadly circulated in the Middle Ages and Renaissance which served as iconographic inspiration to numerous artists. The narrative describes a banquet arranged by a rich Florentine merchant in honour of his patron, Saint Nicholas, for the intention of securing the saint’s protection for his student son. During the banquet a mendicant presented himself at the door begging for charity. The merchant’s young son left the house to fetch him some bread but as we see on the right hand side of the present panel, the beggar revealed himself to be the devil and strangled the youth.

The conclusion of the story was probably represented on a further (currently missing) panel, and might have shown the father beseeching the pity of Saint Nicholas, and attaining the resurrection of his son in exchange for his great faith.

The episode is narrated with lively fluidity: the slender elongated figures harmonise with the architecture they occupy and are similar to those of the five other panels that originally formed the predella.

Bicci di Lorenzo’s polyptych relates iconographically to another example made by Gentile da Fabriano in 1425 for the Quaratesi chapel in San Niccolò Oltrarno (of which the central panels are preserved in the Uffizi, while the predella is divided between the Pinacoteca Vaticana and the National Gallery of Art, Washington), however, the predella by Gentile consists of only five scenes and lacks the episode represented in the present panel.

Bicci di Lorenzo trained in Florence in the studio of his father, Lorenzo di Bicci, during the final decade of the Trecento. In 1404 he enrolled in the Guild of Doctors and Herbalists or Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali and took over his father’s business. He directed a successful studio that was subsequently managed by his son Neri di Bicci; he developed a pictorial language which found great favour amongst his patrons and achieved a fusion between the traditions of the Trecento while gradually making way for the innovations of the Renaissance.

Technical analysis by Gianluca Poldi:

IR reflectography, carried out in two different IR bands, show the existence of a linear underdrawing to outline the architecture and the figures, made with a small paintbrush with black or grey or brown ink over the white preparatory ground. Optical microscopy images suggest the ink used to draw the figures and their detailed faces is brown, containing earths, rather than black.

The modelling of the faces is refined, the painter starts from a partial priming similar to the “verdaccio” described by Cennino Cennini in “The Book of the Art”, he then worked with the brownish under-drawing for various features such as eyes, nose and mouth, and then the artist added some “stains” of colour in three tones of flesh, made with lead white, mixed with vermillion in different proportions: whitish, pink and reddish. Then brown lines were added to define features, the border of the lips and the eyes, the latter finished with black and white.

A few small changes can be noticed, such as in the hands of the central boy dressed in red, on the shoulder/back of the man without a hat and in the hat of the central man with a knife, which was originally different, with a type of scalloped edge. Small corrections were also made in the architecture and the space for the figures: the young blonde figure on the left is partially painted over the architecture of the background door and the staircase. Small holes can be noticed in the paint surface, due to very small bubbles in the mixtures. The tempera hatches are evident in the figures, especially in the lights of the clothes, while the building is obtained with flat continuous brushstrokes.

Unusual features include: the dark brown of the roof made by spreading a layer of finely-ground brown earths over a vermilion red base, with lumps; and there is an unexpected use of red lake to make the shadows of the yellow robe of the central figure. Besides ochre and brown earths, vermillion in brighter reds, and a coccid-derived red lake (presumably kermes) for the pink colour of the boy’s garment on the right and for the shadows, the palette includes lead-tin yellow in the central male figure and natural ultramarine (lapis lazuli) in all the blue areas, comprising the sky and the man´s hat on the left. Small amounts of iron oxides can be found both in the sky, mixed with the lead white and lapis lazuli, and in the cloak of the man at the right of the table, together with some grains of red lake. A few blue and green particles can be found mixed with the pink zones to slightly change the colour.

Esperto: Mark MacDonnell

Mark MacDonnell

Mark MacDonnell

+43 1 515 60 403

oldmasters@dorotheum.com

|

Hotline dell'acquirente

lun-ven: 10.00 - 17.00

old.masters@dorotheum.at +43 1 515 60 403 |

| Asta: | Dipinti antichi |

| Tipo d'asta: | Asta in sala con Live Bidding |

| Data: | 10.11.2020 - 16:00 |

| Luogo dell'asta: | Wien | Palais Dorotheum |

| Esposizione: | 04.11. - 10.11.2020 |